Being Smart Just Doesn’t Cut it Anymore

“Soft skills get little respect, but they will make or break your career."

We all know that one kid from school who blew the competition out of the water. Whether they achieved a 99.95 ATAR, a perfect SAT score or 5 A*'s, they were a level above everyone else. No doubt they will go on to have successful careers; they'll probably earn some money, have some power and perhaps make a difference in the world. But they won't necessarily have the most impressive career of all your schoolmates.

New research by David Deming out of Harvard University says just being smart doesn't cut it anymore. As we move into a world of computational wonder and automation, social skills are catching up with cognitive ability as the most important weapon in the arsenal of a young professional. Wages for jobs requiring high social skills have comparatively increased in the past; this trend is likely to only grow in the future.

Deming's Deduction

For the economists out there, Deming builds a Ricardian 'trade' model to explain how and why wages are becoming increasingly tied to social skills. If you do not understand what that means, that’s probably a good thing.

What you do need to understand is:

Deming considers social skills to do one main thing: reduce the cost of teamwork, allowing more efficient specialisation and collaboration by team members.

On average, your income rises the greater your social and cognitive skills are. Moreover, the higher your cognitive skills, the greater the benefit of high social skills (and vice versa).

The number of jobs requiring high levels of social skills is increasing. This is because jobs with less routine tasks require higher levels of social skills, and routine jobs are increasingly being replaced by automation.

All up, the model argues that in an increasingly competitive labour market, social skills are becoming the most vital part of any employee's skill set, and one of the most important factors in determining an employee's wage.

Deming's Data

So does the data support the claim social skills are increasingly important in labour markets?

The answer is overwhelmingly yes. Consider the (initially daunting) graph below.

The graph compares the change in wages between 1980 and 2012. Each point represents a different occupation. The horizontal axis captures the percentile the occupation was in the 1980 wage distribution. The vertical axis measures the real median change in real hourly wages between 1980 and 2012 for that occupation. The four coloured lines represent the different types of occupations. The 'mathiness' of the job captures how intellectually challenging it is.

Over the 32 year period, the incomes of high social skill jobs increased significantly (for both high math and low math occupations) across the wage distribution — the yellow and green lines are completely above the horizontal zero axis. Notice, there are a lot of blue circles and yellow squares — meaning most occupations are either low-math-low-social or high-math-high-social.

Consider the jobs that were in the 60th percentile of the wage distribution in 1980 (this means only 40% of jobs pay more). If the job required social skills, the real median hourly wage rose significantly. If the job required high math skills but little social skills, the real median hourly wage did not change over the 32 years! If the job required neither math skills nor social skills the real median hourly wage fell!

The above graph demonstrates that over the 32 year period, jobs requiring high levels of social skills saw significant income increases across the wage distribution regardless of whether the job required high cognitive skills or not. Basically, all high social skill jobs saw significant income growth, from minimum wage workers to CEOs.

Jobs that required little social skills but were intellectually challenging (high-math-low-social) were more of a mixed basket. On the whole, these jobs saw little to no wage gains over the 32 year period. Except for the computer nerds at the very top end of the distribution...

Moreover, Deming found the number of cognitively intensive jobs hasn't increased in the past two decades but the number of socially intensive jobs has exploded. What this really means is most jobs that used to be high-math-low-social are transitioning into high-math-high-social jobs. You cant cut it without social skills.

So, when you are trying to pick the kid from school who is going to be the most successful — don't necessarily think of the smartest kid — think of the very smart kid everyone liked.

Let's look at why.

The rise of automation and the two paradoxes

Machines are getting smarter by the year. They can perform routine and repetitive tasks more efficiently and more cheaply than humans can. Many people are getting pushed out of their jobs from the rise of automation; this rise is only in its infancy.

So what jobs can shield you from the rise of automation? Unsurprisingly, it's those that need high social skills. The reason behind all this is summed up pretty nicely in these two interesting paradoxes:

Polanyi’s paradox: This is the phenomenon where we know more than we realise or can explain to others. Try to explain the rules and structure of the English language. You probably can't. But you still know how to write a perfect sentence. This relates to...

Moravec’s paradox: In robotics and AI, logical reasoning and deduction don't need much computational effort. But, observation and perception by machines need a lot more computational power. At least for now, we can make computers phenomenal at processing information and completing complex routine tasks, but we can't yet make them understand emotional nuances such as the anxiety you have over whether or not your flight home for Christmas will be delayed.

The Turing Test: Can machines act like humans?

As one of the 20th Century's greatest minds, Alan Turing is known as the father of theoretical computer science and for cracking the Nazi Enigma code in WWII. He created the Turing test which determines whether a machine is capable of thinking like a human. Turing said, if a machine could convince about 70% of people it was a person, it had sufficient social skills.

Many people have tried creating machines to do just that. The closest any machine has ever come won the Loebner prize in 2014. When mixed in with a bunch of other chatbots and humans, it convinced 33% of judges it was human. The machine could only do this though by pretending to be a Ukrainian boy with an extremely limited grasp of English.

Basically, it cheated.

So, despite what everyone claims, machines are still a long way from pretending they are human. This means as machine-based innovation continues to ramp up, more and more, the only jobs that won't be automated are the ones that need strong social skills.

Deming's paper shows how jobs that are routine generally don't need social skills and the jobs that need social skills generally aren't routine. As jobs become less routine, social skills become increasingly necessary.

Social skills are only going to get more important

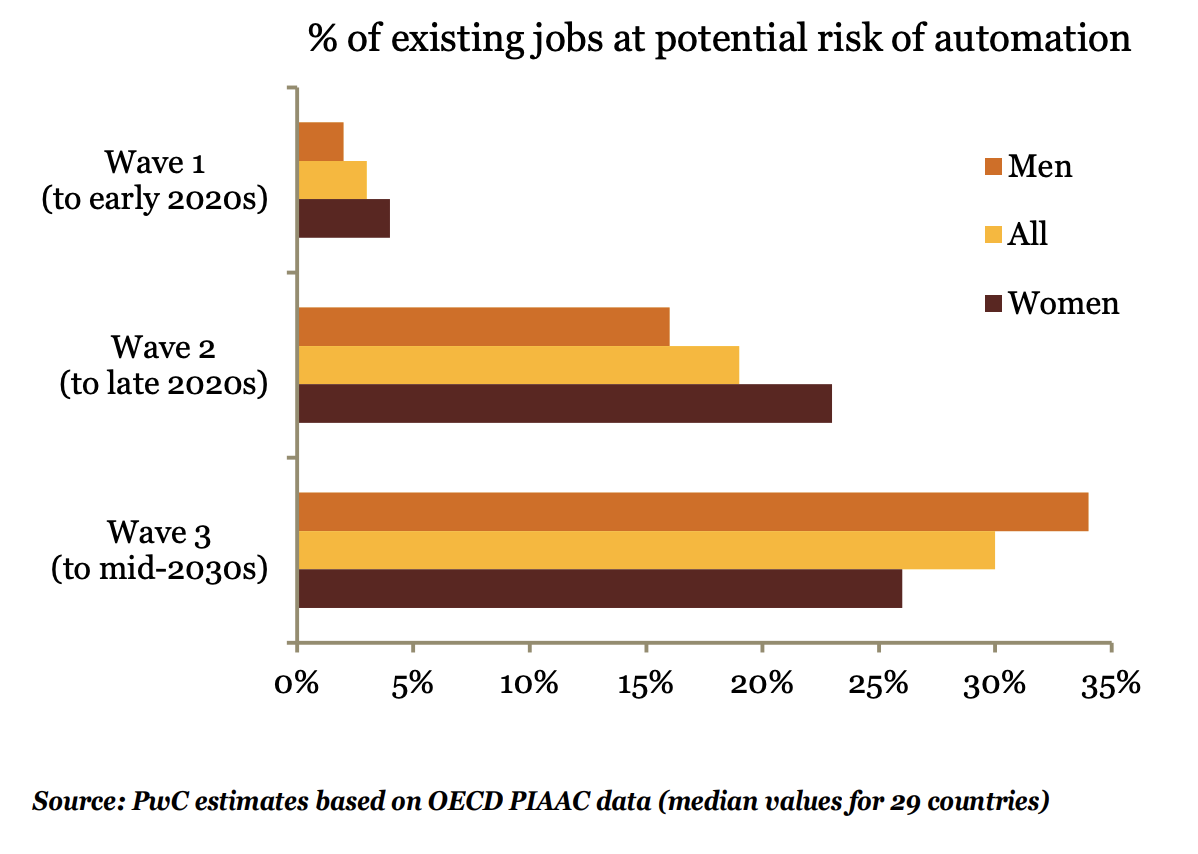

Research by PwC argues we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg of automation and job losses. If PwC is correct, social skills are going to become increasingly important and probably a requirement for almost all jobs. All the data we have shown was only a result of Wave 1 automation. Wave 2 and Wave 3 are going to completely change the structure of the labour market — and in more ways than anyone can predict.

Takeaways

So what is the big takeaway? Social skills are going to become more important than you probably think — so make sure you have good social skills!

However, that’s not the only takeaway. Deming makes an interesting observation in his paper.

“The female advantage in social skills may have played some role in the narrowing of gender gaps in labour market outcomes since 1980.”

Deming, and many other economists, have shown women have on average better social skills than men. As the rise of automation continues, the gender pay gap could flip the other way — a first in history.

As well, these trends can possibly explain increasing income inequality, increasing social polarisation and even increased political extremism. But we will leave those for you to think about by yourself.

Alternative data is taking the financial world by storm