A Marriage of Misinformation: How The Guardian Got It Wrong

“Your wedding's been cancelled by the coronavirus lockdown? Good.”

This was the title of an article written by the Guardian at the height of the 2020 COVID lockdowns discussing the mass cancellation of weddings.

The article sought to explain the results of a headline-grabbing 2014 paper by Andrew Francis-Tan and Hugo Mialon. In their paper, the duo provides evidence that

“Marriage duration is inversely associated with spending on the engagement ring and wedding ceremony.”

As The Guardian says — “The more you spend, the shorter the marriage lasts”.

Now, this paper was a sensation. It is currently the ninth most downloaded paper on the largest public database of academic papers in the world (SSRN).

But are the authors correct? Are shorter marriages associated with more expensive weddings? Yes — well, sort of. As you will see, it’s very complicated.

One thing we know sure, The Guardian’s quote “The more you spend, the shorter the marriage lasts” is absurd.

We are going to try to do something a bit different for this article. Instead of taking a research paper and explaining it, we have formed our own thesis and will use the research results (or lack thereof) to back it up.

The thesis this week: research results are complicated and can be misleading, especially when the media get involved.

Why did the paper make headlines?

You are probably wondering — is it surprising more expensive weddings are associated with shorter marriages? Prince Charles and Princess Diana spent 60 million pounds in 1981 money on their wedding — that marriage seemed to last a grand total of 3 minutes.

The thing with research is, results depend on your method. A simple one to one comparison actually contradicts The Guardian: expensive weddings on average are associated with longer marriages. But Francis-Tan and Mialon’s results made headlines because their method took education, income, religion, children and other factors into account.

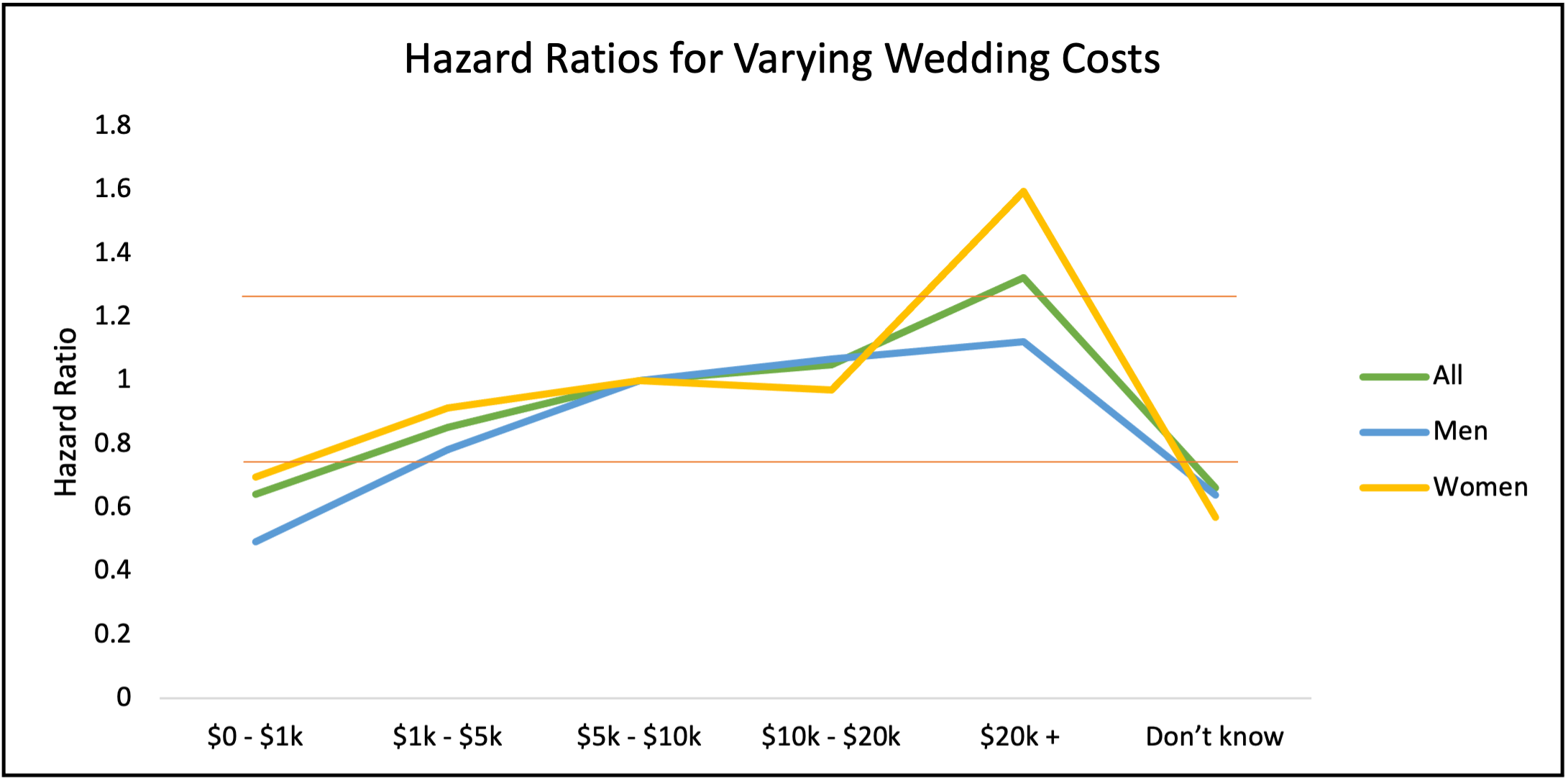

The graph below shows the papers main results.

The horizontal axis captures the amount of money spent by a couple on their wedding. The horizontal red lines represent the level of statistical significance for the ‘All’ category. Hence, only wedding costs outside of the band are deemed to have marriage lengths statistically different from those of the reference category.

As the cost of a wedding goes up so does the couples ‘hazard’ of divorce. Here, the hazard ratio captures the relative likelihood of divorce occurring in any given year in comparison to the $5k - $10k reference group.

So, the $20k + group has a hazard ratio of 1.4. These couples are 1.4x more likely to file for a divorce in any year in comparison to the reference group.

It is clear there is a genuine upward line indicating higher wedding costs are associated with shorter marriages. But you would be mistaken if you thought this was the whole story. As we will see the data supporting this claim is anything but clear.

Problem 1: good sample or bad sample?

When we think about data we think about cold hard facts; a perfect lens that allows us to look at the immutable truths in the world around us. In reality, data is riddled with observational, recording and sampling errors, among many.

So, why don’t we do the proper due diligence The Guardian should have done?

Francis-Tan and Mialon paid $0.5 to $0.75 to 3,370 respondents through mTurk (the Amazon version of Airtasker) to complete their 40 question survey. After that, they removed all respondents who used non-US IP addresses, were homosexual, got married younger than 13, or were older than 60. What they were left with was the data set they used in the paper.

Basically, their data was wholly unrepresentative.

First, they restrict the data collection to mTurk users — who are certainly not representative of the US population. Then they pay these people next to nothing to complete the survey. Would you complete a 40 question survey for 50 cents? We suspect those that did either had too much free time or were in desperate need of money.

So, instead of saying “marriage duration is inversely associated with spending on the engagement ring and wedding ceremony”, the guardian should have said

“marriage duration for under-60, US-based, heterosexual, time rich or cash poor mTurk users is inversely associated with spending on the engagement ring and wedding ceremony”

Would they though?

Francis-Tan and Mialon find that “Relative to the largest US study of ever-married individuals (ACS), our sample is younger, whiter, more educated, and less wealthy”.

Hmmmm…

Problem 2: what about the outliers?

In science, there is a very important and too often overlooked property of statistics called robustness.

Robustness measures the sensitivity of a statistic to changes in the data set. A robust result is reliable because the introduction of a rare outlier to the data does not impact that result, while a non-robust result is unreliable because small changes to the data can disproportionally impact that result.

Unfortunately we don’t have access to the raw data to consider how robust the results are. Be that as it may, we suspect removing outlier weddings that cost less than $300 or more than $100,000 (the Diana weddings) would change the hazard ratios.

The authors use multivariate regressions to build their hazard ratios, which are incredibly non-robust and have been found to be wildly inaccurate in the presence of even one outlier.

So, really The Guardian should have said:

“marriage duration for under-60, US-based, heterosexual, time rich or cash poor mTurk users is non-robustly inversely associated with spending on the engagement ring and wedding ceremony”

We can’t comment on how the lack of robustness affects the results. Though, it does mean the results are drastically less valid.

Problem 3: inflation shmation?

The first two problems are endemic in modern research. Good data is hard to find and robust results are even harder to build. However, there is another big gaping hole in the centre of Francis-Tan and Mialon’s research — they do not account for inflation.

The paper compares the expenditures on weddings across time as if they are the same. A wedding in 1985 that cost $5,000 would cost $15,000 in 2020.

It is the largest flaw in this paper.

Non-inflation adjusted wedding expenses across time are not comparable, and yet the paper does exactly that.

It is entirely possible the negative association between wedding expenditure and marriage duration disappears when you consider:

Weddings (in nominal dollars) are more expensive now than they were in the past

Average marriage lengths have been decreasing steadily over the past 50 years as more couples file for divorce

Maybe the recorded association is entirely explained by the fact modern weddings cost more and modern marriages are shorter, but we doubt it.

At no point in the entire paper is the word ‘inflation’ ever mentioned.

So, really The Guardian should have said:

“marriage duration for under 60, US-based, heterosexual, time rich or cash poor mTurk users is non-robustly inversely associated with inflation-unadjusted spending on the engagement ring and wedding ceremony”

Problem 4: Chinese whispers?

Bad news travels faster than good news. It is one of many social phenomena which represent arguably the biggest problem for the academic sphere — information is spread poorly.

If you were to hear the results of the paper from a friend at the pub, your aunt at Christmas, a brother in law at Ramadan or a colleague at work, it is likely you have been misinformed.

Phrases such as “Shorter marriages have more expensive weddings”, “Expensive weddings have shorter marriages” or even “Expensive weddings cause shorter marriages” are likely to be thrown around. All of which are wrong. The first two are wrong because a one to one comparison shows the opposite. The last is wrong because correlation does not imply causation (see our Noble Prize article).

Think back to the Guardian quote, “The more you spend, the shorter the marriage lasts”. Assume this is all you were told about the paper. You not only fail to understand what the paper says, but you never appreciate the limitations of the research itself.

The Chinese whispers effect will ensure the general public never know the truth.

This is especially true for research like this one, where the results are hidden behind non-laymen statistical methods. Be careful and skeptical when anyone tells you a ‘fact’, even when you got it from the media.

Let’s cut the authors some slack

To the credit of Francis-Tan and Mialon, they do recognise some of the limitations in their research and are careful in their paper to note this. The paper does also identify a reasonable suggestion as to why expensive weddings are associated with shorter marriages — debt stress.

That is, they find evidence more expensive weddings are more likely to cause acute financial problems for newlywed couples, and these financial problems can drive early divorces. However, they add that more research is definitely needed to properly prove this.

Switch your brain on, fool!

Our desire for simplicity and clarity derides the complexity inherent in truth.

Every time someone says ‘research suggests’ we believe it whether it be social pressure or personal doubt. This makes us vulnerable to spreading, misinterpreting and purporting half-truths and wonky facts. Be skeptical about a fact someone says if it doesn't seem right or doesn't add up.

For a lot of us, we need to raise our threshold requirement for believing something. Just because your aunt at Christmas quotes it, a journalist says it or even if an academic publishes it, it doesn't mean it's true.

As Voltaire said:

“Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.”

Like having an expensive wedding just to make your marriage shorter…

Alternative data is taking the financial world by storm